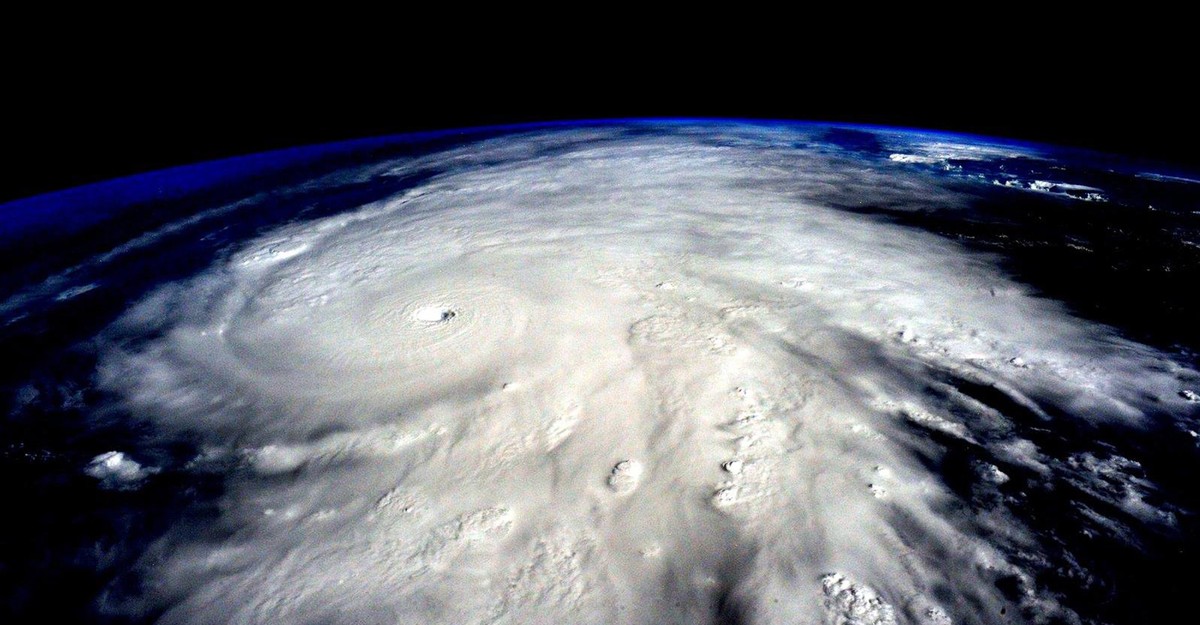

At 149 miles an hour, the world’s quickest curler coaster, System Rossa in Abu Dhabi, is so fast that riders should don goggles to guard their eyes from the wind. However even the formidable System Rossa isn’t any match for the 157-mile-an-hour-plus winds of a Class 5 hurricane, which might collapse a house’s partitions and collapse its roof. And but, in line with a brand new paper, Class 5 might itself be no match for a number of latest hurricanes.

Proper now, each hurricane with most sustained wind speeds above 156 miles an hour is taken into account a Class 5 on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale—whether or not it’s blowing 160 mph, like Hurricane Ian, or roughly 215 mph, like Hurricane Patricia, which struck Mexico in 2015. To tell apart between excessive storms and, effectively, extraordinarily excessive storms, James Kossin, a distinguished science adviser on the local weather nonprofit First Road Basis, and Michael Wehner, a senior scientist finding out excessive climate occasions at Lawrence Berkeley Nationwide Laboratory, explored including a hypothetical sixth step to the size. Class 6 hurricanes, they write, would embody winds above 192 miles an hour. By their definition, 5 hurricanes—all of which occurred in in regards to the earlier decade—would have been categorised as Class 6.

When Kossin and Wehner ran local weather fashions into the longer term, they discovered that if international temperatures rise 2 levels Celsius, the chance of Class 6 storms would double within the Gulf of Mexico and enhance by 50 % close to the Philippines. “Including a class higher describes these fairly unprecedented storms,” Wehner advised me. Really altering the Saffir-Simpson scale would require analysis into how a revised system would talk catastrophe threat, the authors famous within the paper; nonetheless, “we actually ought to think about the thought of scrapping the entire thing,” Kossin advised me. And he’s not the one one who thinks so. “I’m undecided that it was ever a extremely good scale,” Kerry Emanuel, a number one atmospheric scientist at MIT and the editor of the paper, advised me. “I feel that possibly it was a mistake from the start.”

The Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale hit the meteorological scene within the Seventies, when a civil engineer (Herbert Saffir) and the top of the Nationwide Hurricane Middle (Robert Simpson), teamed as much as design a easy one-through-five score for a hurricane’s potential to trigger injury by relating wind pace, central stress, and potential storm-surge heights. For just a few a long time, issues went easily. However by the mid aughts, it was clear that the size’s classes didn’t all the time mirror the injury on the bottom. Hurricane Charley, in 2004, weighed in at Class 4, however brought about comparatively little destruction. Hurricane Ike, against this, made landfall close to Galveston, Texas in 2008 at solely Class 2, however killed 21 individuals straight and brought about an estimated $29.5 billion in damages throughout Texas, Louisiana, and Arkansas.

The distinction was water. Charley, regardless of its excessive winds, was a comparatively dry storm; Ike brought about a 20-foot storm surge. Sandy wasn’t even a hurricane when it flooded 51 sq. miles of New York Metropolis, casting the ocean into the streets, overtopping boardwalks and bulkheads. About 90 % of hurricane deaths within the U.S. come from storm surge and inland flooding, Jamie Rhome, the deputy director of the NHC, advised me in an announcement. In 2010, the NHC tweaked the size’s title to the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale, eradicating storm surge and central stress to make clear that it couldn’t measure a hurricane’s total potential destruction.

However Saffir-Simpson is deeply embedded within the public psyche. Just like the Richter scale’s 9 or the DEFCON system’s one, individuals have a tendency to think about Saffir-Simpson’s 5 as a definitive rating of hazard. “The simplicity of the size is each a flaw and a bonus,” Brian McNoldy, an atmospheric scientist on the College of Miami’s Rosenstiel Faculty of Marine, Atmospheric & Earth Science, advised me. Class 5 is visceral in a manner that inches of rain and projected toes of storm surge maybe will not be. However Saffir-Simpson is so misunderstood that in displays, McNoldy likes to inform individuals: “There’s extra to the story than the class.”

The NHC, which forecasts and communicates hurricane threat to the general public, has tried to increase the general public’s focus from the actual Saffir-Simpson designation. As an alternative, the middle has emphasised hurricanes’ many extra hazards, akin to rainfall, tornadoes, and rip currents. Rebecca Morss, who based the Climate Dangers and Choices in Society program on the Nationwide Science Basis’s Nationwide Middle for Atmospheric Analysis, advised me that including a Class 6 might flip the main focus away from these many different risks.

For its half, the NHC appears unenthusiastic about including a Class 6. “Class 5 on the Saffir-Simpson scale already captures ‘catastrophic injury’ from wind, so it’s not clear there can be a necessity for one more class even when storms had been to get stronger,” Rhome, the NHC deputy, mentioned. A sixth class wouldn’t essentially change FEMA’s preparations earlier than a storm makes landfall, both, as a result of the company anticipates that any Class 4 or 5 storms may have important impacts, a spokesperson for the company wrote in an e mail, stressing that emergency managers ought to think about total dangers from a hurricane’s hazards.

Atmospheric scientists and meteorologists have tried to create higher programs, primarily based on floor stress to raised predict storm surge, or built-in kinetic power to raised estimate storm dimension. However even with a system that comes with wind pace, storm surge, rain, and different elements—finally, “you’ll encounter a storm that breaks the principles,” Emanuel advised me. A perfect hurricane alert, Morss mentioned, would inform individuals in regards to the dangers they might face of their particular location and the way they will defend themselves. It will additionally level them towards dependable sources of correct, well timed data because the storm approaches. “It’s tough to try this with a single hurricane-risk score,” she advised me.

Emanuel and others imagine that america might stand to be taught from the United Kingdom’s system, which categorizes extreme climate as both yellow, amber, or crimson—the place crimson means residents are in imminent hazard. That coloration alert is accompanied by a “crisp narrative,” he mentioned, summarizing what individuals can anticipate to see—as an example, just a few toes of flooding, a storm surge, heavy rain, excessive winds. This type of people-centered hurricane system would require enter not simply from scientists but additionally from communications consultants, sociologists, psychologists, and individuals who have lived by hurricanes. Making a system with that diploma of nuance would take some time, and within the meantime, Saffir-Simpson is the perfect we’ve received. “We need to stick to what individuals know till we now have one thing higher,” Kim Wooden, an atmospheric scientist on the College of Arizona, advised me.

Lengthy earlier than there was Saffir-Simpson, there was Simpson, a 6-year-old watching the water rise outdoors his household’s house in Corpus Christi, Texas. His father hoisted him on his again they usually swam three blocks to security within the city courthouse. However even Simpson couldn’t have imagined the sort of storms we face at present, Emanuel mentioned. In actual fact, it’s exceptional that he and Saffir gave us a succinct strategy to describe one thing as advanced as potential hurricane injury. Kossin advised me he has nothing however admiration for the work of Saffir and Simpson, whom he met again within the Nineties. However at present, armed with extra a long time of knowledge, possibly we are able to construct one thing even higher.