New York Governor Kathy Hochul unfurled a subway “security” plan final week. It included assigning 750 Nationwide Guard and 250 state police and Metropolitan Transit Authority officers to the subway—along with the 1,000 NYPD officers the mayor added in February—to examine riders’ baggage. The governor insisted that her plan is designed to guard New Yorkers and preserve them using the trains. “My No. 1 precedence is the protection of all New Yorkers,” she stated. “Downstate,” she stated, “doesn’t operate and not using a wholesome subway system that folks trust in—I’ve to do that for them.”

As a lifelong subway rider right here in “downstate,” I can inform from her plan that the governor has solely a restricted understanding of what we want in the way in which of “a wholesome subway system.” I immigrated to the town in 1994 at age 7, and have been taking the subway—largely by myself from the very starting—within the three many years since. I rode by means of the late Nineties, when the transit system noticed an all-time excessive in recorded crimes; into 2020, when ridership dropped; and thru 2021, when anti-Asian assaults rose. The governor’s plan does dedicate $20 million for 10 groups of mental-health staff, which could possibly be useful (assuming these groups actually do get susceptible New Yorkers much-needed assets). However the remainder of the plan doesn’t appear to ponder how the subway system works in observe. How do bag checks stop individuals from carrying weapons of their pockets or below their garments? How does one effectively administer honest checks in a system that sees 3 million riders a day, and numerous congested stations throughout rush hour? How can law-enforcement omnipresence in high-traffic stations in high-income areas supply something to far-flung, low-traffic stations, which rating worst on security and harassment?

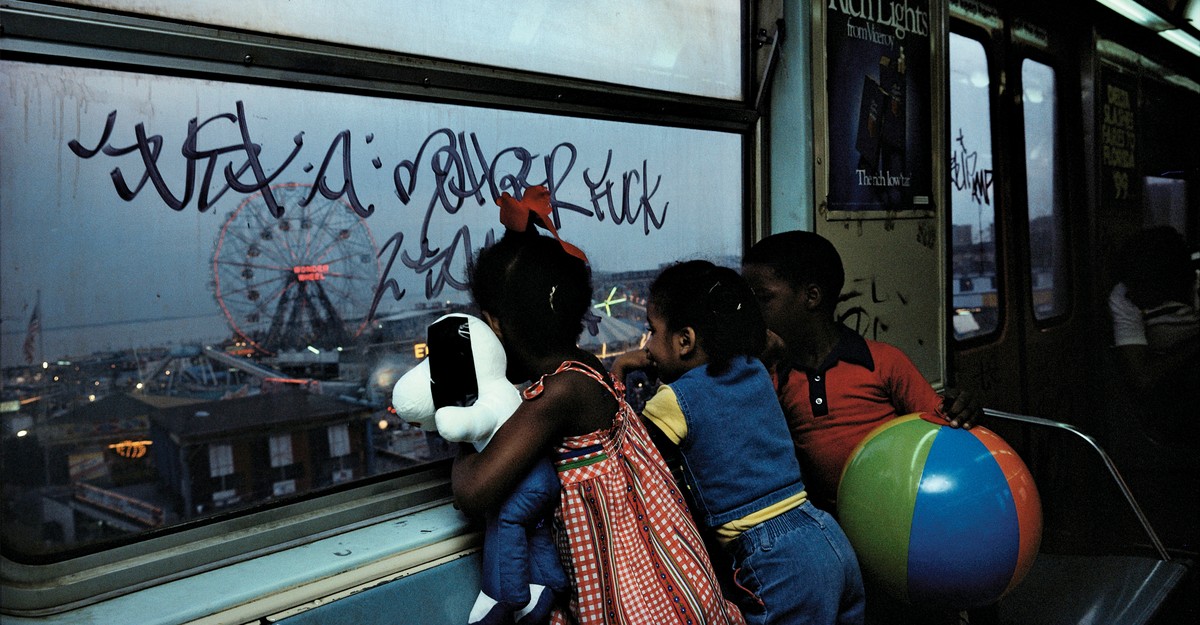

And the plan misapprehends what makes riders really feel protected: not cops or troopers, however fellow riders. Ask any New Yorker what they love concerning the subway—and what makes them really feel most secure down in these busy tunnels—and they’re going to say the neighborhood of their fellow riders. The kindness of the brisk good Samaritans who cease simply lengthy sufficient to hold baggage up the steps and not using a phrase; the infectious vitality of dancers who carry showtime to automobiles and platforms throughout the town; the laughter exchanged after sharing a really New York second of dodging a subway rat. Nowhere on this checklist is the presence of nationwide militia and state legislation enforcement—no, that could be a burden, not a perk; we journey the subway despite, not due to, such options.

As for the purported lack of security, it’s unclear whether or not that’s actual. Mayor Eric Adams stated on social media the exact same day the governor introduced her new plan that transit crime final month was down 15 % in contrast with the identical month final yr (homicide, shootings, and automobile thefts are additionally down). He declared that “the most secure huge metropolis in America simply bought even safer.” The governor’s intervention in our metropolis’s lifeblood is maybe an unsurprising political transfer in an vital election yr. However at what price? Each automobile and platform holds New Yorkers who may benefit from no more policing however extra public companies—that’s, extra funding for the general public libraries, for which the price range was slashed so tremendously that each one Sunday hours have been eradicated, and for which the mayor simply this week proposed additional cuts that might additionally remove Saturday hours; for emergency mental-health-personnel coaching applications, the price range for one among which was lately decreased by $12 million; and certainly, for the subway itself, a public good that belongs to all New Yorkers no matter race, revenue, or standing, and that faces its personal budgetary threats.

In 2020, when white-collar New Yorkers had the privilege of abstaining from the subway, their poorer, extra marginalized counterparts continued to take the practice as a result of they’d no different selection. These are the very people whom the governor’s plan may deter from using the subway: Folks of coloration, as an illustration, are way more more likely to be stopped by legislation enforcement, to be criminalized and institutionalized. The governor’s plan compounds present structural boundaries to fairness and justice.

After which, after all, there are the undocumented New Yorkers, of whom I was one. After I was rising up within the ’90s, using the subway to the general public faculty the place I used to be fed the free lunch that stood between me and hunger, my largest concern was seeing cops within the subway.

I nonetheless keep in mind the primary time a cop stepped into my automobile once I was on the F practice, heading from East Broadway to the tenement-style dwelling my mother and father and I shared with different immigrant households in Brooklyn. I used to be in a packed rush-hour automobile; there was scarcely flooring area for the shuffle of ft as passengers bought on and off. My mom was with me that day, and once I noticed the uniformed officer embark, I grabbed her hand with out turning to have a look at her. I listened to the blood dashing in my ears in the course of the lengthy minutes because the practice descended decrease within the tunnels, below the East River, after which rose once more on the opposite facet, the place, at York Road, the doorways pinged open. The officer stepped out.

It was then that I regained my senses, and realized with a begin that my mom was not in reality the place I believed she had been. After which, a beat later, I noticed that the hand I had been holding was not hers. I nonetheless keep in mind trying down on the hand and tracing it as much as its wrist, elbow, and shoulder, earlier than lastly arriving on the face of its proprietor: a lady I didn’t know, whom I’d by no means seen earlier than and haven’t seen since, however who gave me the warmest smile.

That smile made me really feel protected. In a metropolis with restricted area for a poor, hungry, undocumented child, the subway grew to become one among my few havens. The subway saved me fed and educated. The subway is the place I first learn a few of my very favourite library books, instructing myself English one phrase at a time; it’s the place I wrote the primary draft of my childhood memoir, tracing and therapeutic my deepest wounds; and it’s the place I first began to grasp what dwelling may really feel like in America. After I learn the information final week, a kaleidoscope of subway recollections performed in my thoughts, and I questioned how I’d react to the information if I have been nonetheless undocumented, nonetheless dwelling in poverty and concern.

The governor emphasised that she shouldn’t be forcing anybody to bear bag checks. Those that refuse to undergo a examine can “go dwelling,” she stated: “You possibly can say no. However you’re not taking the subway.” The place, I ask, does that go away the numerous New Yorkers for whom the subway is the one manner dwelling?